| 1949:

Ted returned to Montreal. The political climate, which drove him out of the U.S.A.,

the virulent anti-leftism, was almost as rabid in Canada, though hidden. The Royal

Canadian Mounted Policy (the RCMP) had become a secret police. They compiled 800,000

files on more than a million Canadians - every communist, socialist, outspoken

liberal, union organiser, peace activist, and indeed anyone suspected of any left

wing sympathies. The small enclave that sprung up around my father in Mimico (just

outside of Toronto) in 1950/51 was known in the RCMP files as "Little Moscow".

When a family friend, the young Brooke Forbes, came back briefly in the late 50s

to Canada from London the RCMP visited her to tell her menacingly, "We know

who you've been seeing." We were all quite clear that they must have meant

my family.

Even in the best of circumstances

making a living by writing takes more than talent and dedication. It can take

some luck, and the witch-hunts cancelled out much of that. In a conversation with

Trudy Ship, Ted told how, "Even though I wasn't a member of the Party in

'54, the RCMP turned up at the CBC and said I was a member. The CBC threw me out

of a job, but then re-hired me as a Freelancer." This conversation took place

in 1993 in LA at Julie's Christmas party. Trudy is a close friend of Julie's.

Here Trudy was inquiring of Ted about his relation to her father, Reuben Ship.

Ted taped the conversation in which he recounted how Reuben had written a show

called "The Life of Riley" - that was a very popular radio comedy show

and he was really one of the top comedy writers in the country."

Trudy

asked, "Why didn't you look up Reuben and Ada when you came to live in L.A.

in 1945? You knew them when you were in Montreal." After this observation

Trudy asked of Julie, "How old were you when you came to L.A.? Cause we didn't

meet in Toronto until I was 9 and you were 13." Then to Ted, "How did

you know Reuben and Ada in Montreal?"

"I

didn't know Reuben and Ada. I knew Reuben."

"How

did you meet him?"

"We were on the

same hockey team. We were eleven years old and we belonged to a team I named The

Cossacks - I was a secret Russophile even then. Now what happen when I got to

L.A., 'cause I did call Reuben; I called him and he never called back. Later I

asked him, "What happened?" I was a fairly well known Commie, and he

said that he felt it was too dangerous. I was an open Party member in '45. It

wasn't that he was scared. He was being correct."

"He

wouldn't see you?"

"Honey, at that

time, at that time, he would make it a point, with my history, not to see me.

Later we renewed our friendship, which was marvelous."

"That

was later in Toronto, but in L.A. you were living in the same city for three years,"

said Trudy. "Was Daddy a member of the Party?"

"He

belonged to a branch that had to deny that they were members. That was policy,

to deny membership, and be careful about being seen with people like me. There

was strict Party discipline, very crazy Party discipline, but you can't blame

the Party. Everybody was going after Communists. But I didn't have a clue, until

much later when I came to Toronto, when we started to talk about that..."

"When did you leave?"

"The

States? '49."

"And Rueben didn't contact

you again until..."

"You were wondering

why we didn't get together in '45. I'm just explaining '45. By the time he knew

me well, later, I may not even have been a member of the Party, but I was still

a sympathiser. Everything Russia did was absolutely right. Marxism made such sense

when it was analyzed and with what it promised. It made more sense than anything

else at the time, and one felt part of a great leadership, an elite, if you wish.

We were "The vanguard of the working class". It felt good."

Back in Montreal in 1949 Ted earned a living writing copy in a small advertising

agency, and writing and delivering radio talks. He gave talks on Canadian Literature,

on Hollywood, prepared a series of talks on Mental Health, and a series on medical

advances, which included programs and interviews with Hans Selye (who discovered

"stress") and Wilder Penfield (who "discovered" the brain).

From my childhood I recall the magic of the typewriter,

the family totem. And I recall books. Selye's and Penfield's fat textbooks stood

out. Ted was always reading. Always interested in everything new. He kept himself

informed. He had a great regard for human intellect, and for "science".

That dumb matter had evolved from the mud and become "conscious of itself"

was the great wonder. And nothing would eventually escape the power of human understanding.

Later, with the death and the fall from grace of Stalin, and with the eclipse

of the Party and "dialectical materialism" , while never losing his

respect for the rational, Ted became open, broad minded, and intellectually humble.

From my earliest days I remember Ted lying beside

me on my bed and telling me of the power of the human brain, human ingenuity.

"Men will walk on the moon, possibly not in my life time, but certainly in

yours," he told me. That was back in the mid 1940s, and, though I was just

a child, I found that hard to believe. I

have one vivid memory of Ted from Montreal in '49. I was six years old. I had

a second bout of pneumonia. The doctor prescribed one of the then new sulfa wonder

drugs. It tasted awful. I was reluctant to swallow it. Ted shouted and, grabbing

me by the arm, dragged me across the room. A display of massive force. I took

my medicine.

Ted often reminded me of this

incident. He felt it must have made a deep impression on me.

In 1949 Ted wrote "Lies My Father

Told Me" as a short story.

"When

I was younger, about five I think it was, I believed God allowed the children

that he especially loved to die and come to heaven. I really didn't want to live

after my Grandfather died.

I wrote a story about

my Grandfather in 1949 when I was back in Montreal, back in Montreal not through

choice but because I'd been deported from the U.S.A. It was the height of McCarthyism.

America the paranoid: a red under every bed ready to overthrow the government.

Nobody was safe. There was much hysteria, witch-hunting, blacklisting, and general

unpleasantness throughout the land of the brave. And that was why I was back in

Montreal working in a small advertising agency on the corner of Guy and St. Catherine

streets, run by a friend, Sol Pomerance, an unfulfilled genius.

Sol

had a client he figured I could handle - the Montreal Jewish Parochial School

- then in the process of raising money to build a school. I accepted the assignment

and was doing quite well at it, making enough money handling this client and taking

care of a few others, writing funny radio commercials for a men's clothing store,

a hardware store, a gift shop.

I'd already had

a couple of stories published in The New Yorker magazine, and I had read a few

stories on the CBC. My novel of the Spanish Civil War had been published a few

years earlier, so I had what is known as "a bit of a name" in my city.

One afternoon, just after lunch, I was working on

a radio commercial when the phone rang and a man's pleasant, soft voice said,

"My name is David Rome. I'm the editor of the Canadian Jewish Congress Bulletin

and I'd love to print one of your wonderful short stories." I am always flattered

when somebody wants to publish anything I write. The Bulletin, Mr. Rome went on

to explain, could not afford to pay its contributors, except a nominal fee of

ten dollars. This took some of the bloom off it, but I promised I'd look into

my files at home that evening and find something to send him.

"With

all due respect," Mr. Rome continued, "I don't want an old story. I'd

like a brand new story for the Bulletin. I only found out a few hours ago you

were living in Montreal. The bulletin goes to press at seven o'clock tonight.

Could you please write me a new short story? I'll pick up at your office in an

hour or so."

Naturally I laughed and explained,

pleasantly, that I didn't write short stories in this manner. "A short story,"

I explained, "needs inspiration and time. I'll be happy to send you one of

the stories I've already written."

"Please,

a new story," Mr. Rome repeated.

I began

to lose patience. "I don't think you're listening, and I can't stay on the

phone all day." I replaced the receiver in a sour frame of mind, shaken by

the stupidities of people.

It was less than

an hour later that Mr. Rome appeared in my office. He was about thirty-five, portly,

and sweet-faced, by which I mean that he exuded the pleasantness of a man at peace

with himself. I was not amused. "I don't want to be rude," I said, "but

I don't write stories to order in this way! It is obvious you do not understand

the creative process!"

"I'll wait

outside your office," he said affably. The thought occurred to me that he

was deaf. "I love your writing, Mr. Allan. You're a joy to read, particularly

your short stories." I found that irresistible. "I'll wait until five,"

said the indomitable Mr. Rome, and he sat down outside my office to do so.

I closed the door on Mr. Rome and returned to my

desk to complete the commercial I was working on, but I found it difficult to

push him from my mind. A short while later when I went to the bathroom there he

was sitting smiling that smile of awe and admiration, but he no longer looked

sweet to me. He looked stupid and sour.

I finished

my radio commercial. It was almost four o'clock. To this day I don't know why

I did it, but I heard myself sigh, placed a sheet of paper into my typewriter,

without having the slightest idea what I might type out. The first words that

came out were, "My Grandfather stood six feet three in his worn out slippers..."

and the rest of the story just followed. Meanwhile,

Ted continued to struggle with the Bethune material: "I

had started the biography of Bethune in 1942. Through the forties I laboured over

Bethune. I worked for a while with Angus Cameron, then editor-in-chief of Little-Brown.

I wrote some two thousand pages, but found I couldn't finish it myself and got

Sydney Gordon to help me. The book, "The Scalpel, The Sword" appeared

in 1952, has been translated into nineteen languages, and is still in print in

Canada and China. It's

not clear to what extent Sydney was simply an editor, or to what extent a co-writer.

At the time Ted extended to him a co-authorship, and that began decades of animosity

and acrimony between them. They fought over whose turn it was to come first as

author on the title page. They fought over who owned Ted's film scripts on Bethune.

Sydney moved to East Berlin. According to Ted, Sydney produced no further work,

but lived simply to duel over ownership of Bethune. Ted came to view Sydney as

a loathsome parasite. From

notes dated November 5, 1979: "You,

who I have hurt, forgive me as I forgive those who trespassed against me, with

the exception of J.L., the egomaniacal mediocrity, and S.G., the untalented scumbag

my neurotic needs catapulted into a momentary prominence and prolonged pain in

the rectum. J.L. at least had some talent. S.G. had none. He was an incompetent

hack who fooled me with his anxieties. I thought they hid sensitivity. All they

hid was a pathological envy and greed. I learned slowly. He brings the taste of

bile and vomit to my mouth.

After a year in Montreal, we left for Toronto. Ted's brother, Georgie, was working

as a union organiser. At that time he was working in Fort Erie and living with

his wife, Nina, and their baby daughter, Lisa, in near by Crystal Beach, across

the lake from Buffalo. We stayed with them for a couple of months during this

resettling.

Ted found a bungalow to rent just

outside of Toronto, in Mimico, on the "Longo Estate". Longo was a Construction

Magnate, and his private estate, twenty acres on the lake, had stone walls, landscaped

gardens, a mansion, stables with an in-door arena, several terrace rows of houses,

and our deep red (or maroon) brick bungalow with it's own garden leading down

to the lake. Across what must be the Humber bay, one looked on Toronto. The Royal

York Hotel, rising several hundred feet, was the skyscraper then, "the tallest

building in the Commonwealth". Mimico, now eaten right into the belly of

the con-urbation, was at that time a separate town.

My

father had a large circle of friends. Ted had charm. He was loud and daring, but

with taste and humour. Slowly, as one house after another on the estate came free

to rent, we were joined by these friends. The Jordons, he was a singer: the Pearces,

he an actor, and Uncle George moved up to Toronto. My cousin Paul was born on

the Longo Estate. We lived there two years, 1950/51, and '51/52. I was seven and

eight years old. Again I've few clear memories of Ted. I can't remember where

he did his typing. Was he still working in the kitchen?

Walking

home from school one day some boys stole my hat and threw it into a tree. I came

home distraught. Ted accompanying me back to the scene of the crime. The thieving

boys were still there. Ted insisted they retrieve the hat from the tree. I remember

few details, but I know I was deeply embarrassed.

Ted

wrote that I opened a door in the house at Mimico catching a kitten's paw beneath

the door and breaking the kitten's foot. Ted told Julie and I that the kitten

might have to be put to sleep. "Why?" asked Julie. Because it might

not be able to hunt mice and run away from dogs when it grew up. Julie said that

didn't matter: she would look after it. The kitten recovered. If I remember correctly,

though, this kitten was taken with us in the car when we drove to visit someone,

and lost at a stop over.

During this era some impresario brought a touring group with Musicals Comedies

to Toronto. These "Broadway" shows were performed in a circus tent.

There we saw Brigadoon and Finian's Rainbow and Carousel. A taste of the culture.

We also went to union picnics, no doubt due to Uncle Georgie's connections. I

recall hearing Earl Robinson sing, and Paul Robeson singing on the Peace Bridge.

Classical music, folk songs, and Broadway Show music were important in our house.

We subscribed to an edition of Audubon prints. We

cut them to put them up in the panels of the glass door that then screened off

the back patio as a room for visitors. And Ted's sister, Sadie, came to stay with

us. Among Ted's

notes is a memo to a Dr. Kalz, dated Feb. 25, 1951, that expounds on his family's

ongoing saga: "...As

children, the three of us (Ted, Sadie, Georgie) expressed our hostility mainly

toward our mother, blaming her for my father's illness. We complained, echoing

his complaints, that she "nagged" him too much. She was a perpetually

high-strung and nervous woman, becoming more so over the years. She was a "screamer".

It seemed quite impossible for her to speak in a normal, quiet tone.

My

mother considered her life a failure: her husband was crazy; her eldest son (me)

was a struggling writer; her youngest, a union organizer; and her daughter had

turned out crazy too. The daughter had gotten married, but then divorced when

her child was two years old.

Lately, though,

mother reconciled herself with regards to her sons, for each seemed, in her terms,

to have achieved a modicum of success. Each had a car, a seemingly happy marriage,

children. Only the daughter's life now seemed a total failure. In 1950 the daughter

returned from Los Angeles in a bad state of depression and was given shock therapy.

The daughter lived with the eldest son for a few months. Then he, I, moved my

family to Toronto and the daughter moved in with her parents.

For

the last three years my father had been "well". Three years ago he underwent

shock therapy at the Allen Memorial Institute, but he did not finish the treatments,

complaining that they hurt him. He eventually came back to "normal".

With each succeeding breakdown my father, in his normal periods, appeared a more

and more defeated man; quieter, his sense of humour gone; and he expressed this

by telling me, "I've learned not to worry over silly things anymore. I just

try to take things as they come."

When

my sister and her child moved in with my parents, my mother complained that she

found it hard to take care of Susan (my sister's four year old child). She (my

mother) seemed to be getting increasingly impatient: the child wouldn't eat, the

child wouldn't sleep. My mother complained of being tired. In the meantime my

sister went to group therapy, and at home was completely dependent on my mother.

Two months ago my father came home from work, placed

his head in his hands, and said he didn't feel well and wasn't going to work.

He didn't want to go out of the house. My mother's reaction was, in her own words,

"I got a shock. I saw he was getting sick again. I began to itch that day."

My mother's skin condition has become steadily worse, spreading over her back

and under her breasts. The itching is so bad that she finds it difficult to sleep.

Various doctors told her it was (a) psoriasis (b) nothing. After Dr. Kalz saw

her the first time, she was convinced that he, in the manner of skin doctors,

would keep seeing her often, that she'd spend too much money, so she went to another

dermatologist at the Jewish General outpatient clinic. This was where she was

told she has psoriasis.

When I discovered that

she had been going to other doctors (after I had sent her to Kalz) I became angry

and insisted that she return to Dr. Kalz. Kalz at this time felt that his fears

concerning her condition were confirmed, that indeed she was suffering from Pemphigus

(2), and that she should be hospitalized. When

she told the doctor she couldn't stay in the hospital because she had to take

care of her husband, her daughter, and her daughter's child, Kalz told her that

her life was more important than the taking care of a grandchild. This frightened

her. She thought it meant she had skin cancer. I pooh-poohed her fears, told her

not to be silly, assuring her of Kalz's eminence in his field. In the hospital

she entreated me, "Take me out of here. Don't go back to Toronto without

taking me out of here. If you don't they'll take me out dead," I teased her

about her fear of a simple skin disease.

From

hospital she phones home every evening to make sure that everything is going right.

Before going into hospital she made arrangements with an old friend of hers to

come and cook for my father and sister. Since my mother went into the hospital

my father's mood, after the first day during which he seemed more depressed that

ever, has picked up a little. (I should report here that among the first words

he said to her when she told him she had to go to the hospital was, "What

will become of me?") But today (Sunday) when I told him that he must try

to sound confident and cheerful when speaking to mother, he replied he would try

and that he would tell her he was working and that everything was going to be

fine.

Now, I have tried to characterise in a few pages a situation which, to do it justice,

calls for a novel. I've tried to outline the main features of my mother's life.

To me, my mother's skin has gone insane. This is my mother's way of telling the

world she's had enough and more than she can bear.

I

feel that while ACTH and/or cortisone may bring about immediate relief, my mother

should be treated in the same way a manic-depressive is treated after shock therapy.

The shock therapy in many cases removes the symptoms of the disease; then psychotherapy

tries to play a role in removing the causes. But my mother is not a good candidate

for psychotherapy, and the reality of her situation is ever present - my father,

my sister...

Two days before my mother entered

the hospital she stopped taking her skin medication, took a sedative to sleep,

and slept for the first time in two months. She woke without any itching! The

sores on her back had dried up! Perhaps what she needs is sleep therapy?

Incidentally,

I want none of this to be interpreted as indicating any lack of confidence in

Dr. Kalz. I am presenting this as information for his consideration. I am fully

confident in his administration and decisions regarding treatment."

Ted's mother was treated with

ACTH and cortisone. She survived her Pemphigus, but unfortunately suffered, thereafter,

from Cushing's Syndrome, a side effect of cortisone treatment (3).

In Toronto, the Longo Estate, where

we were living, was slowly being pulled down and turned into apartment buildings.

This made it doubly fascinating for the children (we got to explore the buildings

in progress, and to "borrow" bricks and nails and things to build our

own "clubhouses"), but it put a limit on our stay there. Ted and Kate

bought a house, a bungalow, in the newly sprouting suburbs. His brother George

and Nina followed them, moving one street over. Ted had a study built for him

in the basement and an apartment for his parents. Annie and Harry came to live

in the basement apartment. When we were away in the summer on holidays, Grandpa

Harry "killed" my new pet dog. Timmy was a miniature Collie, and a birthday

present. While we were away Grandpa Harry lured my dog across the road in front

of a car. The first car missed. Harry called the puppy again to cross the road

in front of a second car, and this time engineered the puppy's death. He was jealous

of the attention Annie was giving to it, he confessed to her.

Fairholme

Avenue, by Bathurst and Lawrence, was at the edge of the city then. Then, as now,

it had a large Jewish population. Julie, who was thirteen years old, insisted

that we keep our Christmas tree in the basement so our Jewish neighbours and classmates

wouldn't see it. So the Christmas tree was in Ted's study where the children were

sometimes welcomed in "to have some fun." Actually, my recall is not

of fun, but of being put on the spot when Ted turned on his tape recorder, thrust

a microphone into my hand and badgered me to speak.

Ted's

habit was to work deep into the night, and sleep-in in the mornings. I do not

recall the cigarette hanging from Ted's mouth, but photographs from that period

always put it there. Ted said he smoked three packs, and more, a day.

I

remember crawling into my parent's bed in the mornings. Ted was the warmer, more

relaxed parent to sleep beside.

I have a memory

of Ted wrestling with me in the living room at Fairholme, of him pinning me down

and not letting me go. Perhaps it was just a joke, and it was for just a moment,

but it felt overwhelming.

During

these years Uncle Georgie left the union work and went into partnership with Kate's

brothers, Johnny and Mackie, in the tire-retread business. George made a comfortable

living, became moderately wealthy. I remember Uncle Johnny's new Buick, driving

a hundred miles an hour, and sitting in Uncle Johnny's lap to steer the car.

Ted must have continued to write some advertising

copy, for he brought home from a bubble-gum company a sheet of uncut ice-hockey

cards that went up on my wall. And in the summer of 1954, when we went to England,

Ted had worked for the Ocean Line and we traveled first class and sat at the captain's

table. Ted devised

and sold to the CBC a television talk show called "Fighting Words",

and he appeared on the show as a regular participant, debating issues of public

interest. And it was during this these years of Ted's return to Canada that he

wrote his first plays: "The Legend of Paridiso", and "The Money

Makers". The latter was produced by the Jupiter Theatre in Toronto in 1953

starring Lorne Greene and Kate Reid. Al Waxman played the young Canadian writer,

new in Hollywood, sucked and suckered into "ghost-writing", into putting

his name on blacklisted author's scripts. Two years later a new production of

the play was produced in England at the London Arts Theatre.

The

second play, Legend of Paradiso, was first a radio drama, then a TV play, and

then a theatre piece. (Also, later, a novel, but under the pseudonym Alan Mansfield.) In

the 1990s Ted tape-recorded the following: "Susan

O'Grady says Clare Russell (5) flattered me

by calling me a genius; that it wasn't good for me, this "genius". What

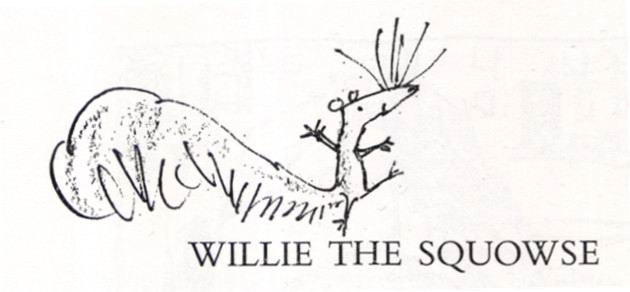

really excites me, when I sold "Willie the Squowse" to Andrew Allan,

when I saw the first rehearsals and listened to every nuance of every word I'd

written, he caught, and the actors caught, it was just exactly as I wrote it.

And then when it went out on the air, I was the narrator, and I was the only one

that goofed. I muffed a line, but it was going out live, even though we were taping

it, it was going out live and absolutely lovely. The excitement, it's akin to

falling in love. It's the way it was when I fell in love, as I have, with Gerda

Taro, with Uta Hagen. Uta Hagen and I intended to marry. I don't know if I was

ever in love with Kate. I think I fell in love with Jeffy. I fall in love a lot

recently: with you (Beth R.), with Susan O'Grady, with Joan D.

One

part of me is really not giving any shit now. Why do I want to write the autobiography?

It's still ego. Sure I want my grandchildren to know, to understand what went

on. So what? I mean, so what if I read a history about the Spanish Civil War,

so what? So fucking what? Here I read Montaigne and St. Augustine's confessions.

There have been incredible autobiographies. It doesn't change anything. Well I

guess I have to face that. Elsewhere

Ted wrote: "During

the Golden Age of Canadian Radio I wrote comedy as well as drama for the Stage

Series, when I worked with the two geniuses who helped me learn my craft, Andrew

Allen and Esse Ljungh. I also performed in many of these shows on radio and television

with performers like John Drainie, Kate Reid, Lorne Greene. Lorne and I became

close. He enjoyed his success as "Pa" Cartwright on "Bonanza",

but when he tried unsuccessfully to play other characters in films, and it didn't

work, he became bitter in his later years. A sad ending for him. He was a very

good actor. This takes me to my television, radio and stage comedy, "Legend

of Paradiso", based on a short story by B.Traven (who wrote Treasure of Sierra

Madre, Death Ship, etc.). The moment Television was born in Canada, money and

the advertising agencies took over. "Legend of Paradiso", which had

been successfully produced by Andrew Allen on his radio Stage series, was slated

for a TV production. We were four days into rehearsals. I'd been paid, the sets

were ready, everything was sailing, when boom, the American Advertising Agency,

representing General Motors sponsoring the TV Drama series, said that the play

"made fun of mass production". It was cancelled! Another play was quickly

substituted. That was my cue to leave Canada."

first

intermission

|

It

won second prize. As a result it was published in 1977 with Quentin Blake's delightful

illustration. (1) It is a simply wonderful

children's stories, up there with Wind in the Willows and Winnie the Pooh is Willie

the Squowse. For this alone Ted should be famous. But it is out of print.

It

won second prize. As a result it was published in 1977 with Quentin Blake's delightful

illustration. (1) It is a simply wonderful

children's stories, up there with Wind in the Willows and Winnie the Pooh is Willie

the Squowse. For this alone Ted should be famous. But it is out of print.